When I was young I didn’t know you could be queer. I lived in a small Catholic pocket of Kansas City, went to school with the same kids who I went to Mass with, mostly Irish Catholic and Latinx families, and heteronormativity was so deeply rooted in the foundations of my family, friends, education, and faith as to render it nearly invisible.

By the time I was eleven I’d read several books with queer characters and themes (Swordspoint by Ellen Kushner and The Vampire Lestat by Anne Rice, at least), but I easily read past anything that would force me to acknowledge my understanding of the world was expanding—the characters just loved each other, and tried to drink each others’ blood sometimes, and I certainly was good at ignoring anything too explicitly sexual no matter what parts were involved in what. To my school’s credit, I remember once the priest told us, probably when I was around second grade, that Jesus loves everybody no matter what, and all we have to do is love everybody in turn. I doubt Father Pat was thinking about the Vampire Lestat or Richard St. Vier but the lesson settled into my mind and I applied it to the world quite generously.

Everybody can, and should, love everybody, believed wee Tessa, even if she didn’t understand very much about love, desire, attraction, identity, or anything. I mean, by the time I was 13 I’d kissed a couple of girls, but they were just practice kisses, and practice kisses don’t mean anything, right? (LOLOL). I didn’t see queer people—or didn’t recognize them when I did—because nothing and nobody ever taught me it was even an option. Of course in retrospect I know there were queer people around me, just very much in the closet because of the Catholic community.

So there I was, burning through adolescence with amazing books, a supportive but oppressively heteronormative community, kissing my girl friends at slumber parties but only so we’d know how to kiss boys when the time came. And I hated my new post-puberty body, all soft belly, too-big breasts, the infamous “child-bearing” hips, but I thought I hated my body because it was soft and fat, and wouldn’t realize for years that I hated it because it had suddenly betrayed me by becoming so overtly, horrifyingly, feminine.

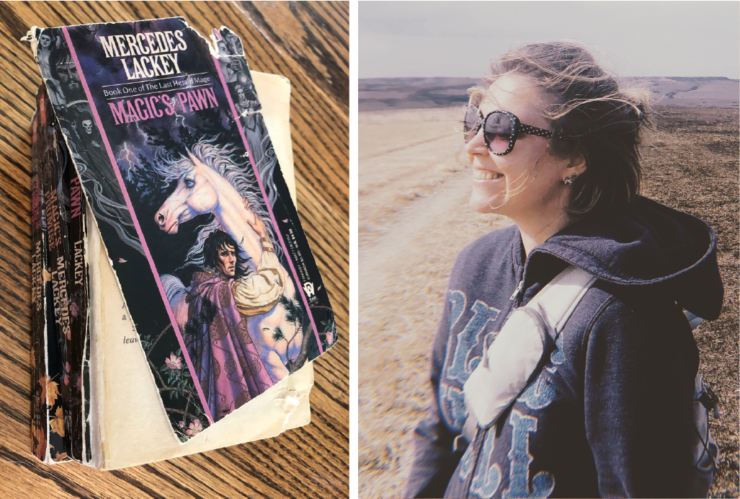

That is when I met Vanyel Ashkevron, the Last Herald-Mage of Valdemar.

I started reading Mercedes Lackey’s Valdemar series for the same reason I suspect many of us did: the magic horses. And the magic horses were great. In each book, a young person was Chosen by a magical horse–a Companion–and discovered they had magical powers. They were brought to the capital by their soul-mate Companion to be trained as a Herald to serve the queen and the people of Valdemar. They grew up to be wise, strong, and brave, and always did the right thing for their country and friends and family, battling tyrants, dark wizards, or prejudice. Though epic and heroic stories in nature, it was the intense emotional resonance of the characters that pulled me through even more than the promise of a soul-bonded familiar or epic magical battles. Today I think many of the books would have been marketed as YA because of the immediacy of the emotional narrative and strong interiority of the third person POVs, not to mention the heroes of most of the trilogies are teens—or start out that way.

Vanyel is the hero of the Last Herald-Mage Trilogy, a prequel series; in most of the books, he’s a long-dead legend. Going in to his story, you know he’s going to sacrifice his life for Valdemar and be the most famous Herald ever.

I met Vanyel Ashkevron when I was just a little bit younger than him. Thirteen to his fifteen, he immediately became my favorite because his feelings of isolation and difference resonated with me; his fears and loneliness and the way he hid behind a mask of know-it-all arrogance to hide his inner turmoil. He was different, and he only needed to find people who could see it.

And he didn’t know it was possible to be queer any more than I did.

I discovered queerness as an identity right along with Vanyel, uncomfortable and intrigued, as his mentors explained to him that being attracted to someone of your same sex was normal, it was acceptable, it was love, even if some people—maybe most people—disagreed. In Magic’s Pawn, the first book in the trilogy, Vanyel is even introduced to an in-world word for gay. In Valdemar, queerness is an identity, something a person is, to the extent that it had a name.

None of this is easy for Vanyel. It’s a fraught, homophobic world he lives in, especially with regards to his family, but he finds friends and mentors who respect and love him, and he falls in love. Everything goes tragically for Vanyel in book one, of course—trauma makes Vanyel who he is, literally: there’s a sort of magical explosion caused by the boy he loves, and the feedback rips open Vanyel’s magical potential so that he very violently goes from having no magic to having All The Magic.

It requires many people working together to help him heal and move forward. The trauma is given weight; healing and choosing to be good, to embrace compassion in the face of tragedy is the point of the book. Trauma and emotional connections, compassion and empathy. But best of all, none of it happens because he’s gay. At the time I didn’t notice that kind of nuance, but in my reread I sure did. None of the bad things that happen to Vanyel throughout the trilogy are in any way punishment for queerness.

Vanyel’s relationship with himself, his sexuality, his family and community are constant struggles throughout the trilogy, as he loves himself, hates himself, tries to reconcile with his homophobic family to greater and lesser extents, all while being the most powerful wizard in the world. It’s as hard and traumatic as it gets, but the result is a full life, meaningful and good. In the end Vanyel is strong and powerful enough to make the kind of sacrifices that matters most: the kind all the heroes make in all the books I loved.

Buy the Book

Lady Hotspur

So here was this character who was powerful, filled with magic, had an epic love story, friends and family both accepting and fraught, a magical horse familiar, he was handsome and clever, and saved the world. And he was gay. His sexuality was explicitly, specifically fundamental to his identity.

I read Vanyel’s trilogy over and over again from ages 13-17. The cover fell off. My cat ate some of the pages. I was obsessed. When I met the girl who someday I’d marry, we were both 15, exactly Vanyel’s age at the start of his book. Though I thought we were “just” BFFs at the time, I also knew we were soul-mates—life-bonded is the term from Magic’s Pawn—and I begged her to read about Vanyel with me. I needed her to love him, because I thought loving him was the key to loving me.

Vanyel was the greatest wizard ever, and he was gay.

When I started thinking maybe—maybe—I was kind of queer, and plagued by discomfort, confusion, and fear that if I let myself pick up what felt like a burden it would ruin my life, I turned again and again to Vanyel. He tried several times to cut off the parts of himself that desired, that loved, that reached out to other people because it felt too hard, which is what I wanted to do. But every time his aunt or his sexy gay wizard mentors or his magic horse convinced him that his whole heart mattered to them, and mattered to the world, he chose connections and relationships. In a way, Vanyel played that mentoring role in my young queer life, by letting me suffer with him, letting me be confused and afraid with him, listening to my struggle because it was his, too, but then reminding me in no uncertain terms that there was nothing wrong with me, and I owed it to myself and to the world to be whole.

I distinctly remember telling myself, Vanyel was a Herald-Mage, and Heralds are Good. It’s their defining characteristic. Vanyel was also gay. Therefore, being gay is Good. That’s just math.

That’s just math!

At some point, probably around grad school, I stopped needing Vanyel. I’d chosen my desires, rather aggressively embraced them, even, and what I needed to keep processing were gender and fluidity issues, which Vanyel, alas, couldn’t help me with. I didn’t read the books again until this week, when I dug out my original trilogy with the torn-free cover and cat teeth marks. I was terrified they’d be terrible, trite, homophobic, and that I was about to ruin some very great childhood memories.

Amazingly, I loved Magic’s Pawn as much as I ever did. Differently, nostalgically, but with just as much passion. I see more now of what that book was doing, on so many levels, and I appreciate it—and who I was when I read it, as well as who it made me. A few times I had to put it down and close my eyes while memories washed over me, things I haven’t thought of about fifteen-year-old Tessa in decades. Pain, longing, hope, and love for who I was, and the struggle I was experiencing.

The second and third books in the trilogy sometimes lean uncomfortably into stereotypes, and book three has a sexual assault that as a grown-ass professional writer I would definitely cut because we don’t need that evidence that the bad guys are bad, but overall they remain powerful stories about strength, magic, duty, love, and queer identity, especially Magic’s Pawn. I truly can’t imagine how much harder it would have been to come to terms with my own sexual and gender identities without that intense connection I shared with Vanyel Ashkevron.

Tessa Gratton has wanted to be a wizard since she was seven. She’s lived on three continents and traveled across more, has a degree in feminism, and once translated her own Beowulf before settling down in Kansas to write and box and create the perfect whiskey cocktail. She’s the author of multiple YA and adult fantasy novels, plus more than a dozen short stories. Her novel The Queens of Innis Lear is a reimagining of King Lear; its standalone follow-up, Lady Hotspur, is available January 2020 from Tor Books. Find her on Twitter @tessagratton.